Five more essential films from South-East Europe

Where to start with Yugoslavian art house film classics?

After great interest in our previous film list, which focused on 5 essential films from South-Eastern Europe in the common Slavic language, in the past two decades, this time we decided to dive deeper and bring closer five more essential films of the Yugoslav region. This time we are focused on films that, in addition to great success on the international festival scene (at major festivals such as Berlinale, Cannes, Venice), gained the title of the art-house classic that bravely poked and questioned the values of time and brought another bolder vision of the world they are coming from.

Underground (1995) by Emir Kusturica

"Underground", Emir Kusturica's metaphorical dark comedy awarded by the Palme d'Or at Cannes Film Festival 1995. examines the Yugoslavian heritage while managing to be more relevant today than ever before. The film follows black marketeers Marko and Blacky who are manufacturing and selling weapons to the resistance in WWII, living the good life along the way. Marko's surreal dishonesty propels him up the ranks of the Communist Party, and he eventually abandons Blacky and steals his girlfriend. After a lengthy stay in a below-ground shelter, the couple reemerges during the Yugoslavian Civil War of the 1990s when Marko realizes that the situation is mature for exploitation once again.

This controversial three-hour-long art-house project initially in the 90's got viewed as Kusturica's definitive goodbye to his hometown Sarajevo and his decay into Serbian national patriotism. Yet. viewed now, more than 25 years later, it becomes obvious that "Underground" is an anti-war and antipolitics film, the story of deception, greed and corruption that had eaten out once a prosperous "utopia". Kusturica finds a way, as always, to place magic realism, "Romani" customs and weddings in his film, making it a ridiculous and yet profound joyride for the art-house audiences.

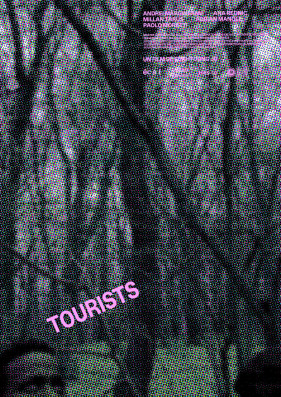

Marble Ass (1995) by Želimir Žilnik

Želimir Žilnik, a key figure in the Yugoslav Black Wave movement, and an uncompromisingly engaged documentary filmmaker who still manages to be constantly on the front lines of current topics, in 1995 made a trip to feature film form with his work "Marble Ass" which premiered (and was awarded the Teddy Award) at the 45th Berlinale. Yet, this decision to do the feature form happened mostly by accident. After encountering a Merlinka, a trans sex worker at the train station one night, figuring out that he filmed her previously under the name Vjeran Miladinović (in the film "Beautiful Women Pass-Through The City") Žilnik began to film scenes from her day-to-day life. As the time passed Merlinka and her trans prostitute friends helped the director to script the story based on their lives in the turmoil of war-infected post-Yugoslavia.

The final product of this one-of-a-kind collaboration, "Marble Ass" is an outlandish, humorous and colourful piece of work that shows the rage and madness of the times. On the one hand, Žilnik presents hypermasculine male clients of trans prostitutes, the early PTSD broken souls, staying relevant to the times and its issues. On the other hand, Žilnik's film manages to be the first full-blooded queer film from the region where LGBTQ people are not there for the laughs, they are not secondary characters, and even though acting might be on the verge of mockery they still are well-shaped and profound.

An Additional Soul (1987) by Ademir Kenović

When it comes to South-East European lost cinematic gems, the first thing that comes to my mind is „An Additional Soul “by Ademir Kenović. This film is the clear culmination of art-house influences of that time, from Otar Iosseliani, Dušan Makavejev to Mohsen Makhmalbaf. The film brings a bitter coming-of-age story about Nihad, the almost fourteen-year-old boy that gets raised in a small Bosnian village briefly after WWII. As the times are changing, industrialisation is coming, the village is getting more vacant and the people are learning how to adjust to the times, from what they can/can't say to what they ought to/not to do.

„An Additional Soul “ is a simple village slice-of-life drama, yet its simplicity grasps the historical context, of the times in which it was placed, as well as the times in which it was filmed. Even though the film focuses on Nihad, it presents the spirit of the whole community, so much so that by the very end the protagonist even seems like nothing more than just a small obedient fraction of a growing and constantly advancing (communist/socialist) whole.

WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971) by Dušan Makavejev

Part documentary on Wilhelm Reich, part fictional story about a Yugoslavian girl's affair with a Russian skater, Dušan Makavejev's "W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism" is an illustrative, thought-provoking art-house film that got initially banned after its release in the early 70's. By dealing with the topics of sexual and political relations in socialist Yugoslavia and presenting the controversial work of Austrian-American psychoanalyst, W.R., director Makavejev makes a rare cinematic gem, topically as well by his cinematic approach. From switches between the real and fictional storyline, assembling the profound subtext upon them to jump-cut editing style that indicates the "action" or "ironic deviation", everything in this film displays the true potency of the film form.

"Challenging" might be the best word to describe this film because, from the historical perspective, Makavejev made something that was out of the common societal values and mindset of the time, a call for sexual liberation in communist countries. Besides this obvious "challenging", "W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism" even to this day tends to challenge cinephiles as well as the young industry professionals as it still serves as a perfect example of how to craft political essay/ docu-fiction/mockumentary.

Frame for the Picture of My Beloved One(1968) by Mirza Idrizović

If you ever wondered what French New Wave would look like if it started somewhere in Eastern Block, Mirza Idrizović’s first feature film brings this imagination to reality. “Frame for the Picture of My Beloved One", made in 1968, brings the story of a group of boys that spend their days in a large yard on the outskirts of the city, entertained by children's games until one day, when a young man, Nikola Maglaj, appears in their lives. After the initial "blow" with Nikola, the boys befriend the man and venture into a pursuit through the complex maze of the grown-up world.

Somewhere on the verge of "The 400 Blows", "Breathless" and "Band of Outsiders" Idrizović's film manages to be a whimsical, poetic neorealist coming of age piece. By following the everyday ventures of boys, the film tends to loosen the imagery of the adult world while simultaneously capturing the essence of growing up in a socialist society. When it comes to New Wave's experimentation, Idrizović chooses a bit more conservative approach. as he focuses on the progressive development of characters, strong, yet ironic, dialogues and engaging storylines rather than the emotion/reaction inducing editing and other film trickery.